The United States had a history of protectionism up until World War II. But since the 1970s, we became active in pursuing free trade agreements with other nations. (Source) Since the 1970s, we have agreed to the free movement of capital, raw materials, and finished goods around the world.

We have also watched our once mighty manufacturing sector atrophy. Jobs in manufacturing were once the definition of middle class stature. No more.

To be fair, manufacturing jobs are declining for more reasons than outsourcing. Automation has had as big or bigger impact on factory employment. Robots now perform much of the work humans once did. But the pervasiveness of "Made in China" on purchases we once acquired from American factories does not pass unnoticed. Many of us have given up trying to "Buy American" since there are so few places to find such goods.

Just this morning, I read that Tesla has opened its first overseas factory. How do we prevent future corporate defections? Bear with me here, but perhaps by importing more workers.

I taught high school economics in a former lifetime and one of the most basic lessons was that there are three means of production: capital (money), raw materials and labor. We have loosened banking, credit and import and export restrictions to allow capital and raw materials to flow freely across borders. But what about labor? Is it "free trade" if only two of the three means of production can cross borders?

For businesses engaged in international trade, the current system probably seems fair enough. But for workers it is not at all fair. There are complications in trade, of course. There were in establishing the free movement of capital which required international currency and investment exchanges. Those are complex institutions. It was complex to set up a system for moving raw materials around the world as well, requiring rules for international and territorial waters, inspections and so on. And we need to add to that international climate change agreements -- much more than the voluntary ones in place now.

So of course allowing for the third means of production, labor, to cross borders will similarly require systems, perhaps equally complex. Labor unions would protest that wages will be depressed as more workers flood labor pools. Anti-immigrant folks may panic. But remember that we already accept highly skilled workers, like software engineers, on special visas. Why? Because there are five software development jobs for every American qualified to fill one. Our H-1B and other visa programs welcome these highly skilled foreigners. Our tech industry could not be what it is without these immigrants. Without them, would Silicon Valley have to pack up and move to Bangalore or Beijing?

So how do we ensure fairness for workers without engineering or equivalent degrees? Some of what we need are political processes, akin to what the European Union (EU) accomplished. The European Union was formed in 1993. Since then, people from member countries have been able to move freely across borders. On the graph below, the EU is the blue line and 1993 is where you see the bottom of the second dip. At that time, employment in Europe was far below that in the US and Japan. Since then (until the 2008 worldwide recession), EU employment has steadily risen while employment in the US and Japan is relatively unchanged. Even after 2004, when the EU accepted several poorer Eastern European nations, EU employment continued to climb.

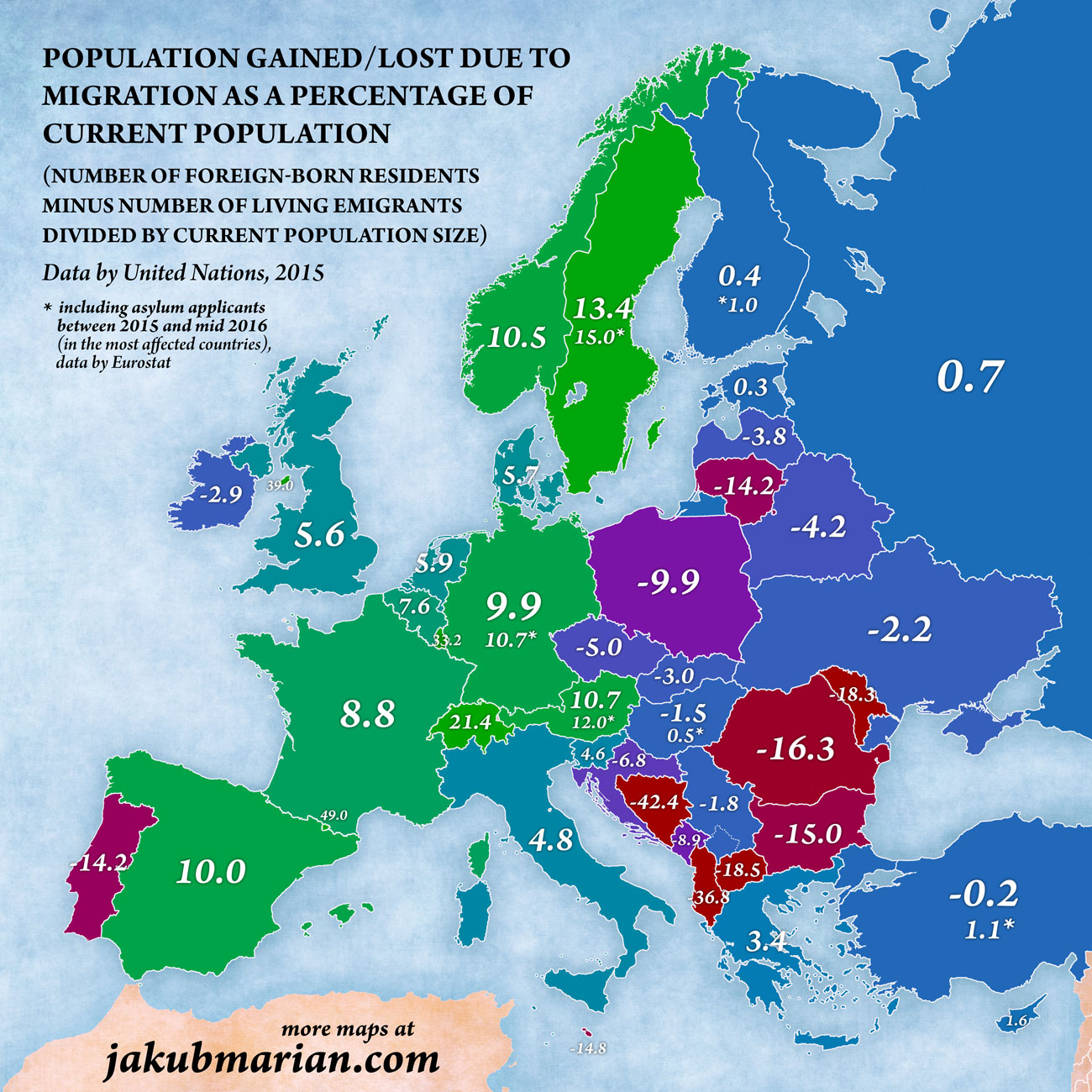

Could a similar North American free exchange of labor work? It might. There are those who fear a wave migration from Mexico and Central America across our borders. But most families migrate only very reluctantly. Moving from your home country is not an easy thing and it takes desperation -- as it did for our ancestors -- to do so. A look at Europe's example is informative.

Note that there is a clear movement from east to west, from less prosperous countries to more prosperous ones. That shouldn't be surprising. But a look at the impact on the nation that has absorbed the most migrants (Sweden) is interesting.

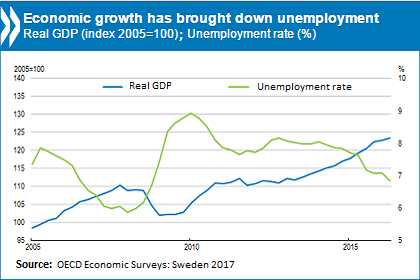

Sweden has the highest rate of in migration in Europe. Yet GDP and unemployment, with the exception of the recession years of 2009-2010, have improved or remained steady. But what about wages? Do more workers mean lower wages for everyone? Sweden's wage growth has exceeded ours, as have other EU countries with higher in migration.

So how do we benefit from the experience of the EU? How do we make sure that real free trade -- allowing not just capital and raw materials to cross borders, but labor too -- doesn't unnecessarily burden the US? The EU can be instructive here also. To become a member nation, applicants must demonstrate democratic principles, the rule of law, human rights, respect for the rights of minorities, and a competitive market economy. They must also adhere to environmental and consumer safety standards and their membership cannot impose an undue burden on other members.

We may wish to adopt some of these and not others. And public pressure would undoubtedly demand we preserve our autonomy and only select those standards that ensure fairness without surrendering self-government. But the EU has demonstrated that in fact, we can have genuine free trade if the will is there. Until we include all three means of production equally -- and that means labor too -- it isn't free.

We have also watched our once mighty manufacturing sector atrophy. Jobs in manufacturing were once the definition of middle class stature. No more.

To be fair, manufacturing jobs are declining for more reasons than outsourcing. Automation has had as big or bigger impact on factory employment. Robots now perform much of the work humans once did. But the pervasiveness of "Made in China" on purchases we once acquired from American factories does not pass unnoticed. Many of us have given up trying to "Buy American" since there are so few places to find such goods.

Just this morning, I read that Tesla has opened its first overseas factory. How do we prevent future corporate defections? Bear with me here, but perhaps by importing more workers.

I taught high school economics in a former lifetime and one of the most basic lessons was that there are three means of production: capital (money), raw materials and labor. We have loosened banking, credit and import and export restrictions to allow capital and raw materials to flow freely across borders. But what about labor? Is it "free trade" if only two of the three means of production can cross borders?

For businesses engaged in international trade, the current system probably seems fair enough. But for workers it is not at all fair. There are complications in trade, of course. There were in establishing the free movement of capital which required international currency and investment exchanges. Those are complex institutions. It was complex to set up a system for moving raw materials around the world as well, requiring rules for international and territorial waters, inspections and so on. And we need to add to that international climate change agreements -- much more than the voluntary ones in place now.

So of course allowing for the third means of production, labor, to cross borders will similarly require systems, perhaps equally complex. Labor unions would protest that wages will be depressed as more workers flood labor pools. Anti-immigrant folks may panic. But remember that we already accept highly skilled workers, like software engineers, on special visas. Why? Because there are five software development jobs for every American qualified to fill one. Our H-1B and other visa programs welcome these highly skilled foreigners. Our tech industry could not be what it is without these immigrants. Without them, would Silicon Valley have to pack up and move to Bangalore or Beijing?

So how do we ensure fairness for workers without engineering or equivalent degrees? Some of what we need are political processes, akin to what the European Union (EU) accomplished. The European Union was formed in 1993. Since then, people from member countries have been able to move freely across borders. On the graph below, the EU is the blue line and 1993 is where you see the bottom of the second dip. At that time, employment in Europe was far below that in the US and Japan. Since then (until the 2008 worldwide recession), EU employment has steadily risen while employment in the US and Japan is relatively unchanged. Even after 2004, when the EU accepted several poorer Eastern European nations, EU employment continued to climb.

Could a similar North American free exchange of labor work? It might. There are those who fear a wave migration from Mexico and Central America across our borders. But most families migrate only very reluctantly. Moving from your home country is not an easy thing and it takes desperation -- as it did for our ancestors -- to do so. A look at Europe's example is informative.

Note that there is a clear movement from east to west, from less prosperous countries to more prosperous ones. That shouldn't be surprising. But a look at the impact on the nation that has absorbed the most migrants (Sweden) is interesting.

Sweden has the highest rate of in migration in Europe. Yet GDP and unemployment, with the exception of the recession years of 2009-2010, have improved or remained steady. But what about wages? Do more workers mean lower wages for everyone? Sweden's wage growth has exceeded ours, as have other EU countries with higher in migration.

So how do we benefit from the experience of the EU? How do we make sure that real free trade -- allowing not just capital and raw materials to cross borders, but labor too -- doesn't unnecessarily burden the US? The EU can be instructive here also. To become a member nation, applicants must demonstrate democratic principles, the rule of law, human rights, respect for the rights of minorities, and a competitive market economy. They must also adhere to environmental and consumer safety standards and their membership cannot impose an undue burden on other members.

We may wish to adopt some of these and not others. And public pressure would undoubtedly demand we preserve our autonomy and only select those standards that ensure fairness without surrendering self-government. But the EU has demonstrated that in fact, we can have genuine free trade if the will is there. Until we include all three means of production equally -- and that means labor too -- it isn't free.

Comments

Post a Comment

I'm interested in your comments.